How pregnancy changes perception

During pregnancy, the perception of and reactions to certain smells and tastes sometimes change drastically. This is also the case in flies. However, what triggers the change in perception is understood neither in mammals nor in insects. We have been able to show in fruit flies that the concentration of a specific receptor in the sensory organs of fertilized female flies increases. As a result, the taste and smell of important nutrients, the polyamines, are processed differently in the brain: Fertilized flies opt for polyamine-rich food and thus increase their reproductive success.

Polyamine intake should be adjusted to the current needs of the body

Pregnancy represents an enormous challenge for the mother's organism. In order to provide the best possible care for the growing offspring and at the same time maintain her own increased bodily functions, her diet must adapt to the changed requirements. "We wanted to know whether and how an expectant mother perceives the nutrients she needs," explains Ilona Grunwald Kadow, research group leader at the Max Planck Institute for Neurobiology.

Polyamines are nutrients that the body itself and also the intestinal bacteria can produce. However, some of the polyamines needed must be taken in through food. With advancing age, the intake of polyamines with food becomes increasingly important, as the body's own production declines. Polyamines play a role in countless cellular processes, so a polyamine deficiency can have a negative impact on health, cognitive abilities, reproduction and life expectancy. However, too many polyamines can also be harmful. Polyamine intake should therefore be adapted to the body's current needs.

Pregnancy can change perception of important nutrients and behavior on them

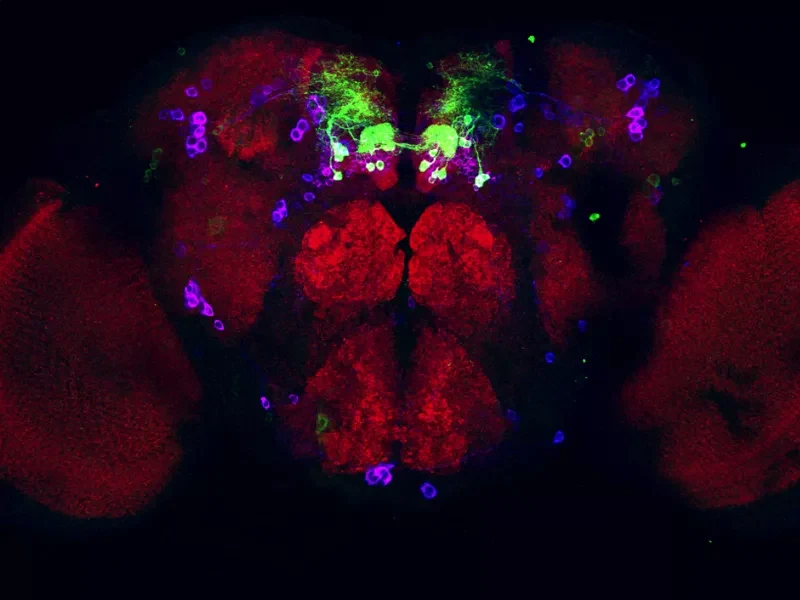

We found that female fruit flies prefer food with a higher polyamine content after mating. A combination of behavioral studies and physiological investigations revealed that the altered attraction of polyamines to flies before and after mating is triggered by a neuropeptide receptor called the sex peptide receptor (SPR) and its neuropeptide binding partners. "It was known that the SPR boosts egg production in mated flies," explains Ashiq Hussain, one of the two lead authors of the study. "That the SPR also regulates the activity of neurons that detect the taste and smell of polyamines surprised us."

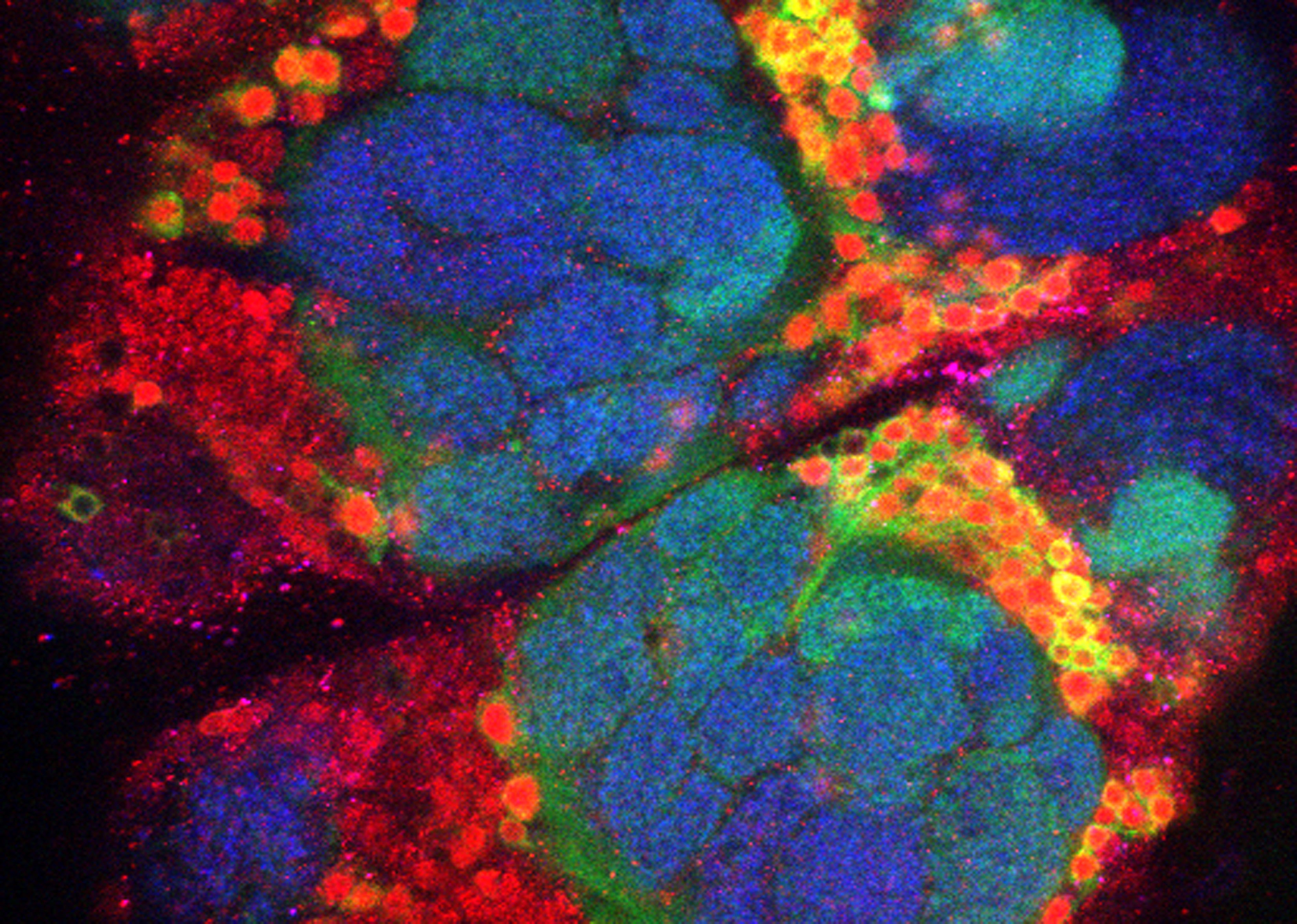

In pregnant females, significantly more SPR receptors are incorporated into the surfaces of chemosensory neurons. Polyamines are thus perceived more strongly very early in the processing chain of odors and tastes. The importance of the receptor became apparent when the researchers used a genetic modification to increase SPR occurrence in olfactory and gustatory neurons of non-pregnant females: this modification was sufficient to make the neurons of virgin flies respond significantly more strongly to polyamines. Ultimately, this led the females to change their preferences and approach the polyamine-rich food source like their mated conspecifics.

The study is the first to show a mechanism by which pregnancy (or gestation) can modify chemosensory neurons, altering perception of important nutrients and behavior in response to them. "Since smell and taste are processed similarly in insects and mammals, a corresponding mechanism in us humans could also ensure that growing life is optimally nourished," speculates Habibe Üc̗punar, the study's second lead author. In a parallel study, the scientists were also able to show how the important polyamines are perceived by fruit flies in the first place.