Decisions in the fly's brain

A freshly brewed cup of coffee smells wonderful to most of us. However, individual components of this scent can be very repulsive on their own or in a different combination. The brain puts the individual components of a scent in relation to each other and evaluates them. Only in this way is it possible to make an informed decision as to whether a scent and its source are "good" or "bad".

The processing of contradictory odors

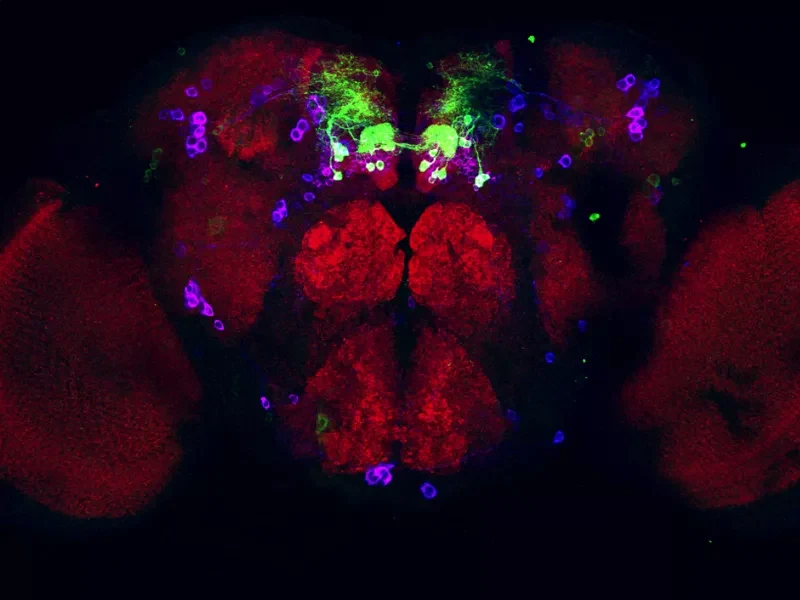

We have discovered how conflicting odors are processed in the mushroom body of a fruit fly's brain. The results assign a new task to this brain region and show that sensory stimuli are evaluated according to the situation. This allows the animals to quickly make an appropriate decision.

Sensory impressions are usually complex. For example, an odorant usually occurs in combination with other odors - the smell of the cup of coffee in question, for example, is composed of more than 800 individual odors, including unpleasant ones. For the fruit fly Drosophila, one such repulsive odor is carbon dioxide (CO2), which is emitted by stressed flies, among others, to warn other flies. When the animals smell CO2, they react with an innate escape behavior. However, CO2 is also produced by overripe fruit - a sought-after food source. Flies foraging for food must therefore be able to ignore their innate CO2 aversion when CO2 is present in combination with food odors. How the brain compares the individual sensory impressions and classifies them according to the situation in order to arrive at a meaningful decision (here: food or danger) is still poorly understood.

"The contradictory meaning of CO2 for fruit flies is an ideal starting point to investigate how the brain correctly evaluates individual sensory impressions depending on the situation," says Ilona Grunwald Kadow. Together with her team at the Max Planck Institute for Neurobiology, she is investigating how the brain processes scents and makes decisions based on them. Now the scientists have been able to show that more complex or contradictory sensory information is processed in the mushroom body. Previously, this area of the brain was thought to be the center for learning and for storing memories. The new results show that the mushroom body has another task: Here, sensory impressions are evaluated independently of learning and memory, and quick decisions are made.

CO2 and food scent release dopamine

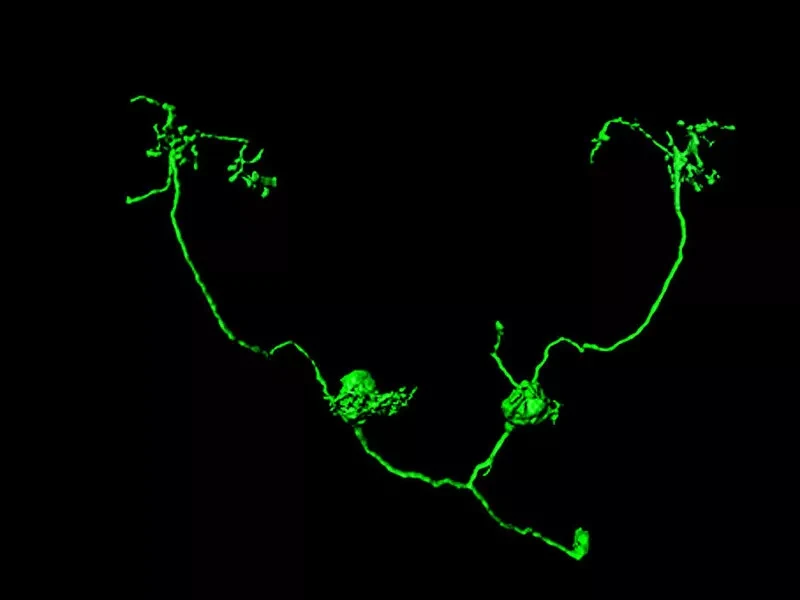

We were able to show that CO2 activates nerve cells in the nerve network, which includes the mushroom body, that trigger the flies' flight behavior. However, when CO2 occurs together with food odors, the nerve cells excite other nerve cells, which release the neurotransmitter dopamine. Dopamine is commonly found in many animal species as well as in humans in association with positive experiences. In fruit flies, these dopaminergic neurons carry the information that food scents are present as well as CO2 into the mushroom body, where they suppress the innate CO2 response by inhibiting "escape neurons."

"Interestingly, the experience that CO2 also regularly occurs together with food scent does not cause the animals to lose their CO2 aversion forever," Grunwald Kadow explains. If the information about the occurrence of CO2 is fed together with food odors into the "learning center" mushroom body, an immediate change in behavior takes place, but no permanent change in the negative evaluation of CO2. This is probably also true for other sensory inputs, for example, the sense of sight. The absence of a permanent behavioral change could be essential for survival in many situations, the researchers speculate: For example, the smell of predators triggers instinctive fear in humans. We do not lose this fear even if we have already seen many predators without fear in the zoo. Here, too, the brain seems to compare and comes to different conclusions, depending on the circumstances.